One of my New Year’s resolutions is to write some book reviews. Just as I said I would last year. I’ve hesitated over it for this long because I find it hard to separate the contemporary books I read with the companies that produce them, and from the work that broke my mind for a while. And I don’t want to be a part of the problem. I know from being inside the industry how much the review system is based on networks and bias. But over Christmas I found a new way to address this conundrum — in fact it practically fell into my hands.

Did you know that if we split up all the land in the UK there’d be enough for half an acre each? Okay, the land isn’t all technically farmable, but still this fact conjures in my mind a misty-eyed vision of a different country, so near and yet so far from our grasp. An expansive, rolling allotment-country where my neighbour gives me freshly laid eggs in exchange for my winter kale and each helps the other through drought and flood. It’s a thought that has followed me this year as I balance out the interior, inevitably commercial nature of my editing job with voluntary work on a local organic farm. I type today with fingernails steeped in Somerset clay.

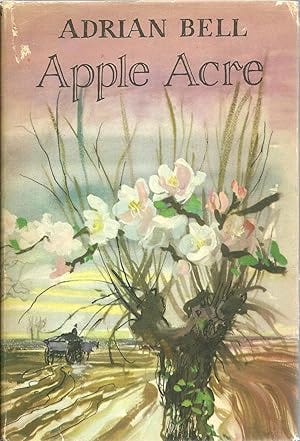

Apple Acre. The words leapt out at me as I browsed the bookshelves in a local charity shop in that sedate moment between Christmas and New Year. The cover showed an abstract apple tree, and opening the fly leaf I saw it was first published in 1942, with the edition I held in ‘64, and it was written by an author called Adrian Bell. It was an account of a year he spent living on an acre in a small Suffolk village ‘so small you would hardly notice it’, during the latter half of the Second World War.

What delight there is in this mode of discovery, unprompted by PR or marketing, un-influenced by social media or Goodreads reviews. A book that sold me on its title and cover, that delivered into my hands the exact words I wanted to read over the holiday and into January, when the apple trees in my own village are blessed during the wassail, and the days lighten towards a slowly beckoning spring. A cosmic alignment of my searching and the world’s providence. It cost £2.99.

We take a risk when we buy such a book. Who knows whether it will give us what we want. But consider this: it has survived, loved, for sixty years. It was reprinted with illustrations for the edition I hold. It won’t disappoint.

The foreword reads just like the accounts of people looking back on that first summer of Covid — at least those who escaped illness — when life was stripped back and the sun always shone. ‘Life was a narrow round of days,’ Bell writes twenty years after the events told, ‘but looking back on them and the straightforward tasks of farming and rearing a young family…I think that, but for the war, they could have been the happiest days of my life.’

Everywhere we look these days we see signs of our tendency towards complication. Technology promising simplicity and tugging us ever further away. My own experience working on the land testifies to the great and absorbing pleasure of practical, useful work that can be seen and eaten. It contrasts with my current editorial work, yes; but my life as a publisher cannot even be measured on the same scale. Yet it seems that this feeling is not exclusive to our current decade or century even. In 1964 Bell was looking back longingly to a past where horses and bikes were the primary mode of transport, and the world was made up of a few square miles but incorporated everything he needed.

Reading his words transports you back to such a world. The war rarely surfaces. Instead, the small trials of winter frost and wet springs. The triumphs of harvest and the joys of a Christmas where the village doctor dresses up and drives a cart with a horse with antlers tied to its head through the village square and the children sing by a great tree, and ‘something lovely that lived in this land raised its head.’ It is an ode to the English countryside, without aggrandization, mud and damp featuring as much as sunrise and nightingale. It is testament to the grounding nature of outdoor work that I recognise myself, the original mindfulness that most of us have lost, where all aspiration is to ‘live in the moment of tilth and green’. Bell’s children feature as well as the land, their enjoyable small trials and tribulations; Anthea, whose best day ever, her fourth birthday, cannot be overshadowed even by one of the worst days of the war. A whole chapter is given to the transportation of chickens, who must be got home with only two bicycles and a cat carrier.

The chapters circle as the mind has a tendency to, as though Bell is telling from memory, aloud. They weave his thoughts on agriculture, literature, history, animal husbandry and society. Flights of fancy trail into observations on winter beet. Field philosophy as its finest. When I read the foreword again I see that Bell was part of a group championing organic growing back in the 40s, though for them it seems to have a much deeper meaning. As with all language, we have commercialised the term, so that is means a very specific, certifiable mode of farming. To Bell and his contemporaries, it meant a more holistic approach that is embodied by the small stories he tells of country life. A common way of being, in the world and on the land, that fosters what our soul truly seeks: community, meaning, belonging.

Cyclical too are our reading habits, it seems. In times of difficulty we look towards nature. In my own time of difficulty in 2020 I read only books about people doing very long walks. I often think there are only about nineteen books out there, nineteen genres, and we discover them anew about every decade. The repetition is part of the healing. Bell writes into a tradition that’s existed since cities began, since Hardy wrote Jude, and continues to this day, with writers like James Rebanks and Raynor Winn. It will doubtless continue, just as we continue to use up the earth ill-advisedly.

Part of me wants to play the cynical reviewer, probe Bell’s motivations in writing this story, his privilege as an outsider coming into the community he writes about, whether the misty eyes are in fact clouded — but that is the beauty of a book discovered in this fashion, in a charity shop, sixty years after it was written, on a cold winter’s day. I can put aside all the noise and take away from it what I will, weigh the words for themselves.

The very last thing I do as I write this article is to look up the book and the author. I refuse to read too much and destroy the charm of my discovery, but I can see that he was a journalist and ‘ruralist’ as well as writer of a few similar books. Some are still in print, and I will seek them out. I hope you might too.

What a thoughtful, lovely review. Henry Mitchell’s books do the same for me: slow me down, reconnect me to the joy of surrendering to time and patient waiting, soothe me with their meticulous consideration of the merits of one variety of cyclamen in a catalogue vs another. Mitchell was the garden editor of the Washington Post for decades, and his writing is elegant, considered, slightly Victorian. His avuncular voice is as comforting as an old woolen sweater. His essays, written pre-Internet, unhurried and unbothered, remind me of our “tendency toward complication” and challenge me to remember that living in my commonly frenetic, mindless state is a choice, even if it feels otherwise. It’s a choice I can resist by digging into the cold red clay of my garden, or methodically sorting the junk pile in my shed, or putting down my phone to watch the birds hop around on the ice that crusts the path outside my window. Thank you for the recommendation.

Ah, I feel such calm coming over me just from reading this, Katy! “The original mindfulness that most of us have lost,” indeed. All the things that pull at our attention, modern life dragging us further and further away from the core of ourselves – being near nature, mind focused on practical tasks yet free to roam, close to the earth that grounds us and of which we are part, always, even though we forget it and fool ourselves into believing we’re well past all that.

I often think this disconnection is such a driving force behind the epidemic of mental suffering – we’ve become detached, and we spend far too much time inside our own fretting minds instead of actually being out there, with dirt under our nails and rain on our faces, belonging.

Reading what you’ve written about Apple Acre makes me think of one of my favourite go-to comfort listens: Alex James’ (the bassist in Blur) All Cheeses Great and Small, read in his own lovely voice. It tells the story of him and his family leaving London and pop stardom for a leaking old Cotswold farmhouse and the adventures of learning to make cheese! :)